Sorry this has been so long coming.

Part of a continuing series of uncertain length on Tomes of Unspeakable Evil and the PCs who love them. I've discussed how people get their hands on such books in the first place, the effects of their dreadful contents on tiny human minds and the purposes and designs of the tomes themselves, why TOUEs exist at all, and last time, the capabilities of evil books.

This time: how to care for your tome of unspeakable evil, and more importantly, how to stop it breaking free and wreaking havoc on the world (before you've had a chance to do it yourself).

There are two main aspects to containment of tomes. The first is straightforward imprisonment, the second is appeasement. Either or both may come into play with powerful tomes. Both sinister sorcerers and do-gooders may need to isolate, control or contain tomes for various reasons.

While I'm technically talking about TOUEs here, in practice most of these could be generalised to all kinds of artefacts, and in some cases to dangerous entities, undead-inclined corpses, and other evil influences too. Of course, they could also be turned around for use by just about any group to contain unwanted things, so a GM might find them handy for imprisoning benevolent entities, or for one evil force to imprison another.

Containment

There are a number of ways you might imprison or otherwise control a tome, which depend somewhat on the genre you're aiming for. Some are period-dependent, others just don't fit with a particular setting. There's also the question of which direction you want to maintain the barrier, which is likely to depend quite a lot on the owner of the tome, their purpose and the nature of the tome itself.

Mundane methods

Let's start off with a few mundane options that are fairly transferable. These need resources, but they don't need genre-specific tools.

Stone walls do not a prison make

To keep something in, or out, there are few options more tried-and-tested than dock-off blocks of stone. A tome could be locked in a tomb (which is poetically pleasing as well as narratively strong) or a similar mausoleum-like structure, where it can't get out unless some idiot breaks through the walls. Alternatively, it could be held in a secure vault or treasury, with thick doors and many locks; this allows you to monitor it and even use it, but also makes unwanted access or escape easier.

If you're not actually a monarch and have to worry what other people think, then vaults can be a problem; mobile or magical tomes might create enough stir to upset the bank, for example, and either get people asking awkward questions, or have people poking into your vault with potentially horrible consequences. This is less of a problem if tomes are known to the public and imprisoning one will be publically acclaimed, although to be honest, openly acknowledging you've got one is just likely to lead to problems: reckless idiots, covetous necromancers or rabble-raising demagogues could all take an interest. What better to attract a party of adventurers? Keeping the thing secret is probably your best bet.

In some cases, a massive iron cage or similar structure might do the job too. This allows you to keep an eye on the tome, while also preventing its escape. Also, large cages are relatively easy to get (compared to vaults, at least), and most tomes aren't physically strong enough to wrench open the bars of, say, a Rottweiler cage. However, watch out for flying tomes that could lift off, cage and all; for tomes that can dissipate into mist; for magical attack, unwanted scrutiny or strangling bookmarks; and of course for excessively widely-spaced bars. Another problem here is that other people can easily see you have a book in a cage, which is often difficult to explain - fine if you keep it somewhere secluded, though. A magical library or magical containment facility might well have cells like this for tomes, though they might prefer something more attuned to the specific capabilities of the tome.

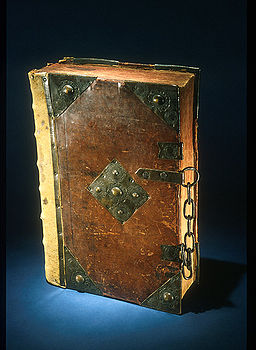

For those not really worried about intruders or observation, who simply want to keep their book from flying away or being pilfered, then you can't go wrong with a massive chain. These allow mobile tomes to take a decent amount of healthy exercise and avoid damp or sunny spots, while keeping them roughly where you put them. They also allow tomes to spring viciously on intruders, useful for sorcerers or avatars of evil who aren't concerned that their tome will betray them. Heavy iron locks are another option, perhaps to prevent biting, speech, flight or spellcasting. This is also relevant for books with certain powers or natures; a book that traps people who touch it, displays sanity-blasting images, or can unleash the creatures illustrated within, is better off bound.

Ring of Fire

A second option is a maintained barrier; something that you can control, but that the tome can't (or won't) cross. Sticking with mundane options, your best bet is fire: keep a ring of flame around a book and it isn't going anywhere. Depending on the setting, this might be simple wood, petrol, lava, or something with a supernatural touch such as blessed candles. These may be more useful than walls for dealing with magical books, which can perhaps exert their influence through stone or spell open locks. On the downside, you need to keep that fire well-supplied. If you have an antagonistic relationship with the book, a circle of fire may be a means of forcing it to obey you, as it could be designed so that if the fire falters it will engulf the book before dying out: this helps discourage unwanted murder attempts, as with nobody to tend the fire, the tome is doomed.

Water is another option, and a moat is a good start. But why stop there? Seal your tome in a guaranteed-airtight box and leave it at the bottom of a tank, where any escape attempt will mean destruction. This is also a good way to conceal its very existence from nosy visitors: a large fish-tank is no cause for concern, whereas a basement dungeon or back-garden furnace may raise eyebrows. At the same time, it's relatively easy to retrieve the book if you need to consult it.

Depending on the nature of the book, it may be that it can be immersed directly in water to counteract its power, without active harm. Ye Tantric Booke of Sexe Magicke is notoriously kept in a vat of crushed ice, which might work for a Slaaneshi tome too. Shadow-magic and similar tomes could be imprisoned by constant light. Some of the more animalistic tomes may be contained readily by barbed wire, electricity or particular scents - incense or herbs. Perhaps salt, silver or some other substance is anathema to it? Magnetised iron (especially for fey-like books)?

Of course, you could also go with something a bit more dramatic, sealing a tome into a block of concrete or some other protective substance.

In principle, you could also set up some kind of elaborate mechanism, so that any escape attempt (or spellcasting) by the book will trigger sawblades, acid, water, paper-eating insects or some other doom. However, I think it's more difficult to make these credible than with an obviously-living prisoner. With a highly sentient book, though, it's a possibility: perhaps a candle needs regularly replacement so as not to ignite something, or a mechanism needs resetting so it never reaches a trigger-point.

In a high-technology setting, there are further interesting options available, of which radiation is the most obvious. Of course, the exact interactions between tomes and technology are too complex and variable to cover here. Similarly, it's much easier to set up monitoring and defensive equipment to watch a tome and to punish (or destroy) it for unacceptable activities.

Guards!

Simple: have some actual people keeping an eye on it. This is very suitable for Warhammer-type settings, as well as some historical ones, where the forces of good lesser evil might assign highly-trained warriors, priests or other trusted individuals to watch a dangerous artefact. Guards can keep an eye on what a tome is up to, which none of the others can, and actively intervene or adapt to thwart plans. On the downside, they're vulnerable to attack, influence or even outright corruption. Assigning multiple guards at a time, and assessing them regularly for signs of manipulation or taint, is advisable.

Overview

Books that are simply pure forces of malevolence, you're likely to want to secure thoroughly. These will rarely (if ever) need consultation, and so walling them up behind fifty feet of stone is probably the best bet. If the book is a useful tool to you, then the priorities are different: you need access to it yourself, so locked doors and cages are more likely. Some books aren't really dangerous to the owner, either because they have the same goals, because the book is fundamentally bound to the owner, or because of the owner's particular nature: in these cases you're mostly worried about escape or vandalism rather than protection, and so simple restraints should be adequate. That being said, even demon-queens may want some minimal protection to reduce the number of servants obliterated by their tome. An owner powerful enough to shrug off magic and rip apart unruly tomes has few concerns, but some tomes may still be so chaotic or plain bolshie that they need imprisoning.

You also need to consider how permanent a containment you're looking for (options for actually destroying books I'll consider another day). A library, powerful sorcerer or religious order may want to contain a tome permamently, either to make use of it or simply to contain its evil. In these cases, you want a solution that can be readily maintained; perhaps one that doesn't need expert maintenance or constant monitoring (though these are impressive for adventurers), and one that isn't likely to weaken over time. In contrast, player characters are quite likely to want to control a tome just long enough to fulfil some objective or find a means to destroy it. In these cases, something effective in the short term is appropriate, and if it's prohibitively expensive or unmanageable for longer use... well, that's their problem. Having players scramble round for oil, buy expensive herbs or rig up steel cages before stealing the sorcerer's tome can be a fun bit of preparation and a chance to show ingenuity.

Magical methods

In a setting where magic is more prevalent, or where PCs are more likely to have access to it, there are also a number of magical options to contain your tomes.

Weave a circle round him thrice

Magical wards and seals are a great option for containing tomes, or at least certain kinds of tome. There are a range of these available. Magic circles and pentagrams are one option; the book itself rests on a pedestal, or perhaps the ward is carved into a marble slab where the book lies. A sort of mobile might hang charms, spell-parchments or magical herbs all around a book, preventing it from using its powers. A book-chest or glass case might be inscribed with charms or covered in sacred wax seals.

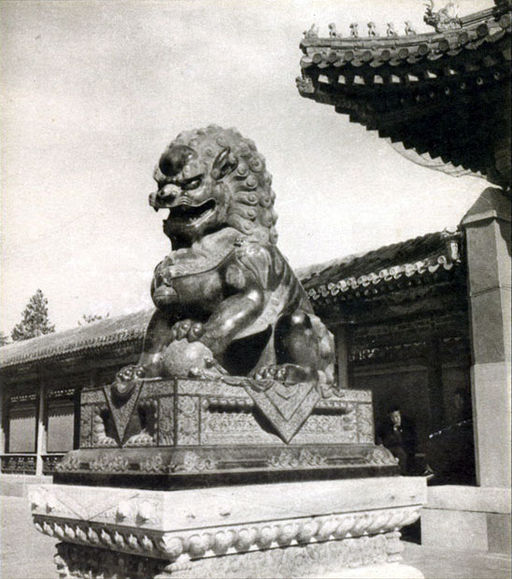

Statues and charms are another form of warding. Perhaps statues of a powerful deity can contain the book's powers - though this doesn't necessarily have to be one you approve of. In a grey-morality setting, characters might be forced to invoke entities they dislike in order to combat those they loathe; on the other hand, a cultist might willingly call on the power of various foul entities to master the tome. Such wards might be subtle (a simple circle of statues) or dramatic (lightning or flame arcs between outstretched hands, a book floats glowing in the centre of the circle).

For a more immediate seal, tomes might be wrapped with strips of holy writ or prayers, sheathed in dragonskin or tied up with prayer beads. More dramatically, a magic sword, unicorn horn or nail from the True Cross might pin a tome down and sap its power, without destroying it.

Conversely, it may seem more appropriate to ward the entire room or building, either because it will affect everything inside, or because it keeps the tome from leaving and that's all that really matters. This may be particularly relevant with toolbooks, whose power the owner wants to draw on, as removing and redrawing wards and seals each time may be very inconvenient. In these cases, doors may be heavy and rune-carved, walls may be made of nullifying substances (see below), and ceiling and floor tiles painted with sigils.

Antimagic

Most settings with substantial magic also have some canonical magic-blocking possibilities, be it antimagic fields, psychic null-zones, octarine, slabs of lead, or divine powers (relics or shrines, perhaps) that suppress tainted magic. In such settings, these may be an obvious way to contain the more magical kinds of tome. They are, however, likely of less use in tackling other hazards: a tome in such a field may still be able to bite, speak or even absorb victims, while its malevolence remains undiminished and its contents still pose a significant danger.

Opposing influences

I mentioned anathemic substances above, and magical versions are just an extension of this idea. Most obviously, there are sacred or magical substances that may hinder a tome, ranging from holy relics to arcane powders. Another option is opposing magical types: for example, a necromantic tome might be helpless in a place redolent with nature-magic.

Guardians

While we've already discussed ordinary guards, magical settings allow for potent entities to keep a tome in check. A whole range of options is available. Mindless skeletons are hard for a tome to influence, but a necromantic tome poses obvious problems there. Paladins, sanctified sorcerers or other empowered mortals can more readily resist a tome's influence and check its schemes. Many magical creations might be suitable guards, be they golems, giant bronze serpents, or weapons imbued with magic and simple commands.

Taking a different tack, creatures might be summoned to watch over a tome, though in some cases that poses its own risks. A benevolent spirit may cheerfully (and safely) guard a tome, whereas a demon is dangerous enough to summon, let alone to leave watching an artefact of incredible vileness. More neutral entities, such as elementals or shadow-beings, may simply be vulnerable to corruption. A sphinx or similar being inclined to guardianship may be a good bet, assuming you can make a deal with it. Ideally, you'd have a powerful avatar of some opposing force to guard the tome, but for many people that isn't an option - even if they exist and the character could contact them, explaining why you've got the tome and why you need to hang onto it may be a delicate or impossible business. A cultist, in contrast, might have one or more powerful evil beings as guardians, relying simply on dominance or on differences of interest to prevent them allying with the tome against her.

Continuous suppression

All TOUEs are nasty business, but for the most potent or pernicious, constant effort may be needed to keep them in check. A constant circle of prayer might be maintained in shifts by members of a holy order, preventing the book from taking action. Wizards might need to regularly reinforce wards or suppressive spells, or psychics might maintain permanent vigil with psionic senses alert for any sinister activity. These are fundamantally a variation on the ring of fire mentioned earlier - a containment technique that calls for constant effort on the part of the warders.

Protection

In many cases, as least part of an owner's concern is going to be keeping people away from the book, rather than vice versa. Whether they're scheming rivals looking to pinch your grimoires, meddling do-gooders eager to quench your plots, sinister cultists trying to retrieve a dreadful tome, or stupid kids who could doom the entire world by their drunken antics, they must be kept away.

Many of the methods I've already mentioned function just as well for keeping out trespassers - thick walls, big spikes and powerful guardians can all be effective deterrents. Since intruders are often more immediately cunning (or unpredictable) in their efforts, having intelligent guards is often a good idea, though bear in mind that guards can be corrupted, bribed, ensorcelled or straight-up killed, while big spikes remain both big and spiky.

Of course, some methods pose problems once devious human opponents come into question. The problem with many defences is that they're obvious, and this tends to attract attention and inspire greed. A book bound tightly in iron chains is, in some people's opinion, just crying out to be read; putting a necromantic tome inside a circle of magical flame in a rune-inscribed granite-walled chamber in a rune-covered cave under a remote mountain just gets them interested. Guards make people wonder what's to be guarded, and locks and wards simply highlight the location of the coveted items.

Camouflage

If you're concerned about meddlers, you may want to look at ways of concealing tomes, disguising their nature and misleading the interlopers. This creates a tension between the desire for serious protection, and the blatancy of such methods.

One obvious option is to hide the needle in a haystack. A well-guarded library is, in some cases, an excellent way to hide a tome. Intruders aren't usually renowned for their patience, and wading through a whole library to find the tome is probably beyond them. However, certain types of tomes make this an undesirable choice, such as those that can devour or possess other books, those that will actively seek out intruders, or that make their own physical efforts to break free. It also isn't likely to work on those tomes that are vast and sinister, burn with unholy light, levitate, whisper and howl, or otherwise draw attention to themselves.

Concealment is another possibility. Confident cults may leave their books lying around on altars, but the wise wizard has spellbooks tucked away for safekeeping. Traditionally, tomes tend to be stashed in secret compartments of lecterns and statues, under large magical symbols that hint at the command word needed to reveal them, in cellars under large rugs, and other prominent locations. These are perfect for some games, but you should vary it by genre. In a light-hearted setting, the book may be hidden under someone's pillow or in a large chocolate box; in a very gritty setting, it may be in a large box-file marked "Utility Bills 2001-3", in a battered cardboard box full of genuine tedious paperwork, amongst a number of other boxes stuffed under the stairs with a stepladder carelessly laid on top of them.

Appeasement

Sometimes, imprisonment isn't on the cards. Perhaps you don't have the resources necessary to imprison a tome, or the means to do so without attracting the wrong kind of attention. If you're always on the move, then you probably can't keep your TOUE in a three-foot-thick steel cage surrounded by a fire of cedarwood and salt. Maybe the intoners' union won't accept 24-hour rotas to maintain your circle of prayer. It's also possible that a book is too powerful for you, or its influences too subtle to confine. Plus, maybe you don't want that kind of relationship: if you need to use the tome for some reason, then there may be no option but to negotiate. Maybe you're not actually working against the tome, but with it, or at least in the same sort of direction. Perhaps you're simply cacklingly evil. In these circumstances, appeasement may be the way to go. Not all tomes will agree to this, but some may be prepared to lie inactive or limit their activities, if various desires are sated.

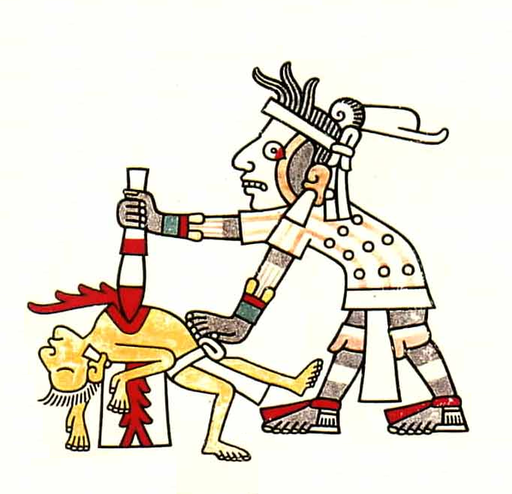

Sacrifice

The classic option, as with any evil artefact or entity, is sacrifices. There are many kinds of sacrifice, from good old killings to life-energy, magical power or knowledge. Some tomes might drain emotions or memories, or dreams. A more corrupting choice might be allowing the tome into a victim, rather than feeding on them: the tome might be permitted to inhabit and control the victim's dreams, to possess their body for an hour a day, or to transform them into twisted minions. Those books that regenerate themselves might prefer some form of energy, while those that wish to spread evil influences prefer to infect new victims. See the post on book vampirism for more thoughts.

Sacrifices are particularly suitable for cults, especially those centred around a tome. They are also likely where the owner of a tome is largely in the tome's control, perhaps unable to resist this demand but not quite weak enough (yet) to give it entirely its own way. The main point here is that the sacrifice doesn't really get you anything except making the TOUE less likely to cause trouble. It's like feeding a captive animal or paying Danegeld.

Bargains

Sacrifices could arguably be lumped in with bargains, but I feel they're worth separating. What I'm getting at here is agreements to exchange services rendered, basically. These are likely to involve more obviously sentient TOUEs, which plan and make deals, whereas sacrifices may be more suitable for more animalistic tomes with less complex sentience.

A fun option is the favour-for-a-favour. The owner of the tome agrees to act on behalf of the tome, if only it will provide the knowledge she needs, or refrain from trying to turn Berkshire into a scorched wasteland full of the laughter of incomprehensible extradimensional beings, or simply stop invading her dreams. In some cases, doing things yourself may be preferable to doing them in your sleep and waking up bruised to see fuzzy CCTV pictures on the telly of you robbing the British Museum stark naked. At other times, the demands made may seem far less harmful than the consequences of refusal: removing that weird stone from that field, performing a little ritual here, they're certainly better than having the tome eat another neighbour. And of course, certain owners have no compunction about doing genuinely evil deeds in exchange for what they want. Sorcerers and cultists of course; but also utilitarians, despotic rulers and the desperate may see such actions as the lesser of two evils, rather than have the TOUE's power loosed upon the world. Of course, the TOUE isn't just asking this stuff for fun (okay, certain ones are); it's making a bargain because it will get something out of it, and little deeds can add up to a mountain of trouble.

Rather than actions, a TOUE may desire stuff. As mentioned previously, Pontius Glaw is a decent inspiration here. This kind of works for any sentient artefact, but especially for things that might be a shadow of their former glory. Prison books are a great option here, as the minds trapped within seek ways to influence the world. Information is a good starting-point, and a gentle way to lead PCs into gray areas - providing a little information about the outside world won't do any harm, after all... after this the TOUE may seek repair, aesthetic enhancement, mobility, special treatment, servants, and so on. If handled carefully, PCs could build up a kind of relationship with a tome and disregard its evil for a time, especially if it seems to play fair and somewhat respects them by not demanding evil deeds and being generally amicable. All the better to betray them later.

I think an important point to make here is that unlike some things I've mentioned in this series, much of this would work very well for tomes that aren't indescribably evil. A spellbook or tome of knowledge might demand particular favours to provide what the reader wants, simply out of pride or towards its own, non-evil ends. More importantly, a benevolent tome is perhaps even more likely to demand services that further its goals, and this may be a way to kick off adventures. Even selfish and mercenary characters can be prodded into doing benevolent things if it will attain their ends, and this might offer the chance for them to develop into more altruistic people - if the players want them to, of course.

Wholehearted Obedience

Don't forget that sometimes the goals of the tome and the owners will coincide perfectly. In these circumstances, just doing what the book wants can keep it perfectly contented (although of course, some contrary, malevolent or inscrutable books may still act up). Or to look at it another way, perhaps the owner's activities are entirely satisfactory, even without conscious effort to appease the tome. This is likely to be the case where books of a particular deity or alignment are owned by followers of that power, where a character has deliberately sought out a TOUE suited to their temperament, or where mysterious fates have conspired to bring together two complementary wills.

Containment in Play

So from a gaming point of view, how are these approaches likely to affect play?

Ownership costs

If a PC owns TOUEs, then there may be considerable practical and financial costs in containing them suitably. Even building a vault will take time and money - potentially quite a lot of both. Any more serious buildings, particularly if warded, may be fantastically expensive. A moat or cage will need to be inspected, just as you might with a wild animal's pen, and runic circles may need cleaning or redrawing regularly to keep them effective. For those interested in playing with such things, I picture the difficulties of maintaining a runic circle to be rather like maintaining canal banks or locks; because you're trying to contain something, you can't simply rub out the chalk and redraw it! You need something like an arcane cofferdam to let you work safely.

Such things as walls of fire or regular sacrifices have ongoing costs, require maintenance and regular inspection to make sure things are under control. If you're using esoteric substances like silver dust, phoenix feathers, blessed candles or rare herbs, it might be difficult as well as expensive to keep the barrier going (silver dust is liable to drift away over time, even if it's not being consumed). For a PC party, that's a great opportunity for some adventuring to restore their supplies. Keeping a fifty-strong choir going all day and night forever is a pretty big undertaking, and I think some serious planning can be expected. In all these cases, having PCs regularly make payments for their containment choices offers a way to make it feel significant and something more than nominal.

Many of the higher-maintenance methods may be a problem for PCs unless they have very reliable staff to help out. A deathtrap that needs resetting once an hour sounds good, but the practicalities are a real nuisance: interrupted sleep, no holidays, and what happens if you're ill? I think it's reasonable to bring these things into play if players decide to use such methods. Even on longer intervals, there are issues - if the PCs are delayed returning from a trip by a car breaking down, does the trap trigger and destroy their tome just to be on the safe side?

Staffing of any kind brings its own problems, whether you're talking about your choristers, some traditional guards, summoned beasts or even just domestic staff in the same house. Trustworthiness is a real issue, and the more staff you have, the greater the issue, not least because more people know and word is more likely to get out. There's always a risk that one of your new choristers is actually a disguised cultist, and it's made much more likely if you're trying to keep a staff of 400 choristers on the go. There's also the question of recruitment, which is not a simple matter: how do you recruit all those choristers? When do you let them in on the issue of exactly what's expected, and what do you do about the ones who don't come up to scratch or don't want anything to do with it when they learn the secret? I feel like recruiting and maintaining staff could be a fun aspect of a TOUE-based game, with opportunities for problems ranging from choosing good candidates to handling illness or stress, dealing with possible treachery, and even everyday HR matters. Sorting out pay disputes or problems in the workplace could be a diverting break.

PCs should also consider testing their protections. Guards may need regular spot inspections to make sure they're up to scratch. Over time, both PCs and hirelings may get lax in their behaviour if the TOUE shows no sign of escaping, which is something I'd take advantage of as a sentient tome. It's particularly likely, I think, with precautions that require a lot of effort. Perhaps the circle of candles isn't quite as tightly-packed as necessary, or the singing is a bit lacklustre. A cage may get rusty, or a box decay over time, or be gnawed by rats - perhaps rats summoned by a tome! You may also want to inspect guards' physical and mental health, to ensure they aren't being corrupted or harmed by the tomes they guard.

Summoned creatures offset some of these issues, but bring their own problems. Negotiating with or appeasing them can be a thorny issue. An unwilling summon might perform its job only sullenly and reluctantly, and secretly hope the tome will escape; some may cling to the letter of commands rather than the spirit. A summon may demand esoteric or vile payments in compensation for its work, while even benevolent spirits might ask for tasks to be completed. Again, these offer a good chance for further adventures while a tome backplot simmers away.

Unless PCs are careful, then many of these approaches might attract unwanted attention from neighbours, the authorities or from sinister enemies. This is particularly true if they're performing sacrifices or buying a lot of strange substances.

Overcoming protections

The other side of the coin is what happens when someone else has a tome the PCs want.

In many ways, the precautions aren't that different from ordinary anti-theft precautions, just with a slightly different focus. Walls, doors and guards are likely to work just about as well - although the locks may be on the unexpected side. Moats and walls of fire keep people out, as well as books.

Actually locating a tome is often a difficulty, and I mentioned camouflage above. However, containment can actually make a TOUE easier to track down: an owner buying lots of arcane components, sacrificed victims turning up nearby, unusually large kennels or a constant drift of cedary smoke can be a useful clue to a tome's location. Similarly, PCs may pick up on the comings and goings of guards, or even on recruitment attempts.

Some precautions don't exactly present an obstacle, but will make it fiddlier to steal or consult a tome without damaging or releasing it. This is true of underwater storage, various kinds of traps and magic circles. A careless attempt to remove the tome might trigger the trap and destroy it. On top of that, the PCs will likely need to have some way to contain it temporarily until they can get it back to their own storehouse. However, methods like the True Cross nail or dragonskin bindings are very portable.

Of course, PCs may want to destroy (or even release) a TOUE rather than steal it, and many precautious will actually make this easier. The traplike methods can be triggered by PCs, while confining a trome and stopping it from using its powers will leave it vulnerable and easy to attack. If PCs wish to release a tome (perhaps to wreak havoc on its cult), then they could interfere with sacrifices, scuff a runic circle or interrupt the supply of fuel to a ring of fire. Some of these could be done remotely, or even indirectly, making it less likely that they'll end up suffering as a result. For example, they could use commercial or logistical approaches to block the supply of cedarwood to a town, disguising it as ordinary commerce, a health and safety issue (insects in the wood?), or even a legal dispute. Within a week, the owner runs out of wood for the fires and disaster strikes - or perhaps they're driven to take some extreme action that allows the PCs to achieve another objective.

And on that last point, it's worth noting that even threatened breach of a TOUE's containment may be enough to achieve the PCs' ends, by disrupting an owner's activities, by forcing them to take illegal action and having them arrested, or simply by distracting them while you achieve your real goal.

Okay, this has got really long and rambling now, so I'll stop, but I'd love to hear other people's suggestions and views here, particularly any ideas for containment types and how you might use them in play.

Tune in next time...

Next up I'm planning to look at actual destruction and disposal of tomes.